A short-lived 'long' jetty in Teddington

All around Lyttelton Harbour are the

skeletons and ghosts of past jetties. The skeleton jetties remind us of what

once was. Of the ghost jetties there is no longer any sign; they have long been

reclaimed by the sea. In Teddington there is a skeleton jetty which might just

as well be a ghost jetty since it is all but invisible to the passing public.

A stream flows past the Wheatsheaf Hotel

and out onto the mudflats. The stream carves a channel which was once a

lifeline for the Manson and Gebbie families who settled at the head of

Lyttelton Harbour in 1845, well before the arrival of the first Canterbury

Association immigrants in 1850. Starting

from scratch the families established thriving dairy farms, later branching out

into sheep. However the road around the harbour to the port town of Lyttelton

was initially non-existent and then, for a long time, little more than a bridle

path. So passage by sea, for farm produce, supplies and visitors, was

vital, though challenging.

Seventeen-year old Susannah Chaney arrived

at Lyttelton aboard the Randolph in

1850 and was promptly engaged by Samuel Manson as a domestic servant. In later

life Susannah wrote...

I went across to the

head of the bay in a whaleboat, and when we went there the tide was out and

there was a big expanse of mudflats. I was taken ashore on a sledge drawn by

two bullocks. There was a tub lashed to the sledge, and on to this a seat was

fixed. Mansons was the first farm I saw in my life.[1]

The mudflats were the problem – and one of

the reasons for the last-minute decision to site the town of Christchurch over

the hill on the plain and not at the head of the harbour as planned. In 1862,

the Manson family, no doubt helped by the Gebbies and other local farmers,

built a 300ft-long jetty (at the cost of £100)

stretching out across the mudflats to access the stream channel. The piles of

this jetty plus the channel markers are still visible.

The jetty was short-lived. On 15 August

1868, an earthquake of about magnitude 9, offshore from the Peru–Chile border,

generated the largest recorded distant tsunami to strike New Zealand. The

Lyttelton Times reported on the 17 August that 'the jetty, 300 feet long, at

the head of the bay had been carried away and that Mr Manson's paddocks have

been flooded.' Sheep were drowned and

the beach paddocks were so salty they were unusable for several years. Seawater

travelled inland almost to the point where St Peter’s Church now stands.

Out on the Teddington mudflats are the remains of a long jetty. I'm unsure whether this is the Manson jetty, destroyed in the tsunami, or a later, public jetty (see next post). What this skeleton does show is the determination of farmers in the area to use the sea as their highway despite the problems of harbour silting.

Out on the Teddington mudflats are the remains of a long jetty. I'm unsure whether this is the Manson jetty, destroyed in the tsunami, or a later, public jetty (see next post). What this skeleton does show is the determination of farmers in the area to use the sea as their highway despite the problems of harbour silting.

|

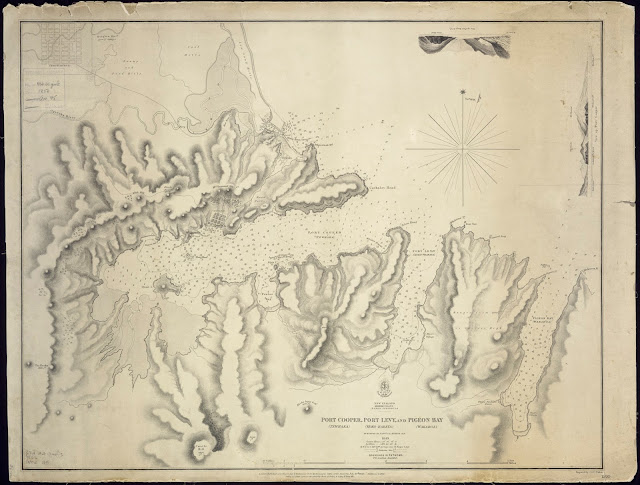

| The mudflats are clearly visible at the head of Lyttelton Harbour in this 1856 map of Port Cooper (Lyttelton), Port Levy and Pigeon Bay (Alexander Turnbull Library) |

|

| Jetty piles at Teddington with remains of the rabbit-proof fence to the left (Jane Robertson) |

|

| Channel markers leading to the Teddington jetty (Jane Robertson) |

[1] O’Loughlin, Janet, ‘Mindful of my Origin’. The Mansons of Kains Hill. Christchurch:

Caxton Press, 2009.

Comments

Post a Comment