Prisoners of very different stripes - Ripapa Island #4

When I began this blog I thought of jetties as benign, welcoming structures. A landing place after a long journey to a new land, a symbol of safety from the storm. I didn’t think then of those in Whakaraupo/Lyttelton Harbour for whom a jetty represented an unwelcome entry to a place they would be kept against their will.

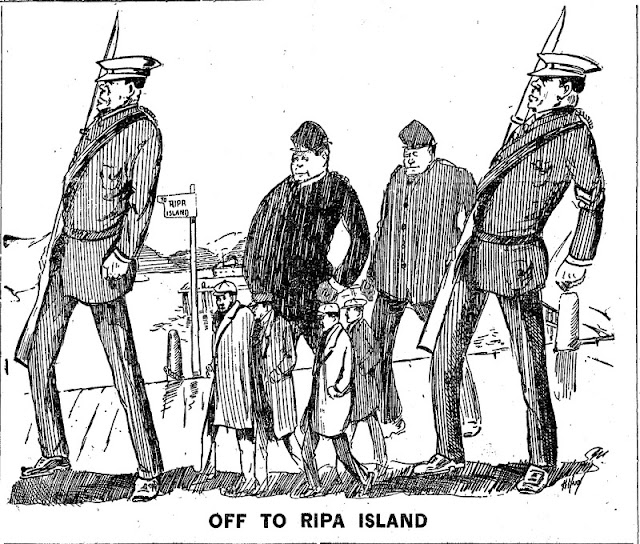

So it was in June 1913 when 13 young men from Christchurch and the West Coast were transported to Fort Jervois. The young men, aged between 18 and 20, were Reg Williams, James Nuttall, Tom Nuttall, Bill Robson, Bob and Jack McTaggart, James Worrall, Ted Edwards, Edward Hannam, Walter Hooper, J. Coppersmith, Henry Guthardt, and H.W. Thackwell.[1] They were passive resisters or, as we would term it now, conscientious objectors, sentenced to 28 days incarceration on Ripapa Island.

|

| Maoriland Worker, “'Off to Ripa Island',” Voices Against War, http://voicesagainstwar.nz/items/show/63 accessed June 9, 2018 |

The Defence Act 1909 introduced a general training requirement for males 12 to 14 years old (Junior Cadets), 14 to 18 (Senior Cadets), 18 to 21 (General Training Section), and 21 to 30 (the Reserve). Men and boys could be exempted on religious grounds if they carried out non-combatant duties within the military. Refusal to comply could result in fines, and potentially imprisonment for those who did not pay them.[2] This was regarded as a possible forerunner to full conscription. Groups such as The Passive Resisters Union, The Peace Council and the 'We Wont’s' rapidly formed, the main centres of resistance being Christchurch and the coal-mining towns of the West Coast.

The detention of the young men on Ripapa Island went relatively smoothly at first. They refused to drill and were not forced to do so. But when they were ordered to clean weapons they refused and were placed on half rations. The men responded with a hunger strike. In the cold winter conditions they rapidly became sick. A court was convened on the island; the men were charged with insubordination and sentenced to another week’s detention. Prime Minister William Massey refused to include conscientious objectors in any exemption to the act because he thought ‘shirkers’ might pose as conscientious objectors. This widely held view was voiced by Colonel Heard in response to questioning by the Joint Defence Legislation Committee.

The presumption is that if these lads on Ripa Island can be successfully insubordinate it encourages lads of the same kidney to become insubordinate also, and the consequences are that in Christchurch you have a very large number of passive resisters who are opposed to any form of military work, not from conscientious objections, I think, but they find they can evade military service and also not be punished.[3]

There was little support for the men in the local or national press. They were regarded as 'malingerers, trouble-makers and notoriety-craving youths' who were using their incarceration on Ripapa Island to broadcast the pacifist cause (which of course they were). However to others they were heroes. On 4 July a letter from the men on Ripapa Island was read at the Labour Congress sitting in Wellington. The delegates resolved

that this Congress strenuously protests against the wicked and barbarous method of imposing solitary confinement on the boys now incarcerated on Ripa Island for refusing military service, and calls upon the Government in the interests of humanity to immediately release these boys.[4]

Four hundred members of the Congress marched to Parliament. A deputation met with the Prime Minister and Minister of Defence. The in-house ‘searching’ inquiry that followed absolved the military and concluded that the young men were only ‘out for misrule’.

On July 23 another Court was held, this time in the Courthouse at Lyttelton. The magistrate dismissed all the charges. Some of the men were released at the end of July, others in late September. James Nuttall, who served three and a half months, wrote in a letter: “We are fighting here, and hope you are doing likewise outside, because we realize that New Zealand must at all costs be freed from the clutches of this jingoistic monster, conscription.”[5]

World War 1 was just around the corner.

|

Socialist Cross of Honour given to James Kirkwood Worrall. Jared Davidson

http://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/radical-objects-new-zealands-socialist-cross-of-honor-and-antimilitarist-protest/

|

Another – and very high profile – prisoner in Fort Jervois was Count Felix von Luckner who, in the SMS Seeadler, sank 14 allied merchant ships in a four-month blitz during World War 1 before his ship was grounded on the Society Islands. Von Luckner made it in a small boat to the Cook Islands and then on to Fiji (an epic journey under the circumstances) where he and his men were arrested. He was brought to New Zealand as a prisoner-of-war; imprisoned on Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf from where he escaped; rearrested in the Kermadec Islands and sent to Fort Jervois along with second-in-command Lieutenant Kirchiess and a third man to act as an orderly. The three remained on the island for 119 days until the Armistice in November 1918.

Ripapa Island was regarded as “the most secure spot in New Zealand for Luckner and his adventurous companions.”[6] On 12 January 1918 the Press reported that

the island, a very appropriate one, is to be especially prepared for the reception of its visitors. A stockade is to protect its edges, and an armed guard, probably of C2 men, is to be placed on the island sufficiently strong to guard the prisoners night and day.

Von Luckner’s daring escapades had been widely written about in the New Zealand press and there was keen interest in the man himself. It was reported that he was to write a book during his detention on ‘Ripa Island’ about his voyage in the Seeadler. “The Count, by the way, is said by those who know him, to be of very powerful physique. So strong are his hands in fact that it is possible for him to bend a copper coin between his thumb and forefinger.”[7] ‘Colourful, charismatic and enigmatic’ are words used to describe him.

There was concern that von Luckner and Kirchiess were being treated too leniently on the island, especially given their track record of daring escape. Commander of the Canterbury Military District, Colonel Chaffey, protested that there was “absolutely no foundation” to such claims. The prisoners were given the same food as the soldiers on the island. They had a stretcher, a wooden chair and a table in each room. They were allowed to read censored newspapers and to write two letters a week each on a single sheet of paper.

None of the prisoners was allowed to go on to the mainland. They had been allowed, however, to have an occasional bathe in the sea under the escort of two sentries with loaded rifles. That was the only luxury they received.[8]

I’m not sure Luckner and Kirchiess would have considered the late-winter/spring sea temperatures luxurious.

|

| Count Felix von Luckner http://navymuseum.co.nz/count-felix-von-luckner/ |

|

| Count Felix von Luckner and Lieutenant Kircheiss on Motihue Island 1917 https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/754zme/count_felix_von_luckner_and_lieutenant_kircheiss/ |

|

| Section from Von Luckner's cell on Ripapa Island. It reads... “109 weary days in this dreary place…we are fed up with this…and off we go…” http://navymuseum.co.nz/count-felix-von-luckner/ |

Von Luckner revisited New Zealand on a lecture tour in 1938. He recalled “the 119 weary days” spent in Fort Jervois. “But after all we had a good time, as Major Leeming in charge of the fortress was a gentleman, and the guards were also good boys. We liked them and so did they us.”[9] During his visit to Christchurch he expressed an interest in revisiting ‘Ripa Island’ but permission was refused for security reasons. This prompted a lively exchange in the local papers between those who applauded the decision and those who regarded it as an affront to the Count. One letter writer pointed out that there was scarcely anything of security value to hide. The guns were in such a bad state of disrepair that they could not be raised from their mountings in the pits and “the only occasion the drawbridge was raised was in order to prevent the dog on the island straying and worrying the sheep on the mainland.”[10]

|

| Press, 9 April 1938 |

The following year New Zealand was once again at war with Germany.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compulsory_military_training_in_New_Zealand, accessed 9 June 2018

[2] Press, 27 December 1913

[3] Voices against war: Courage, conviction and conscientious objection in WW1 Canterbury. http://voicesagainstwar.nz, accessed 8 June 2018

[4] http://heritage.christchurchcitylibraries.com/Publications/1910s/RipaIsland/PDF/CCL

[5] Ibid, accessed 9 June 2018

[6] Press,3 January 1918

[7] Press, 21 February 1918

[8] Press, 4 March 1918

[9] Press. 14 September 1937

[10] Press, 14 April 1938

Comments

Post a Comment