Rāpaki #1: Before the jetty

Most of us know Rāpaki as a Māori settlement set in a beautiful, sheltered bay with a lovely swimming beach, on the northern shore of Whakaraupō. It has a distinctive, well-maintained and much photographed jetty. How and why has this jetty survived in a harbour where so many others have been lost?

The community of Rāpaki in Whakaraupō lies in the shadow and shelter of Te Poho o Tamatea (the breast of Tamatea), named after Tamatea Pōkai Whenua (Tamatea the seeker of lands), descendant of Tamatea Ariki Nui who commanded the Takitimu canoe from Hawaiki to Aotearoa. At some point Tamatea Pōkai Whenua set out to explore the southern island of Aotearoa. On a coastline largely devoid of sheltered inlets, the unexpected bulbous peninsula of volcanic rock with its many sheltered bays would have been a surprising and welcome find. Tamatea must have explored the big inlet on the peninsula’s eastern side (what we now call Lyttelton Harbour) by sea or by viewing it from high on the surrounding hills, since he named it Whakaraupō after the great quantities of raupo growing at the head of the harbour.

|

| Te Poho o Tamatea (the breast of Tamatea) keeping watch over Rāpaki. W. A. Taylor photo, Hocken Collections |

On their return trip overland from Southland, Tamatea and his men were caught in a southerly storm on the hills above Rāpaki. Without their fire sticks they could not survive the cold. So Tamatea appealed to his atua for help and in response came ahi tipua (volcanic fires) from Tongariro and Ngāuruhoe. The fires travelled down the islands, touching the land at various points before creating Te Ahi a Tamatea - the hill next to Te Upoko o Kuri (Witch Hill). Tamatea and his men were saved by the warmth. The fire continued down the hill, into the sea and across to Ōtamahua (Quail Island), where it burnt the cliff black. The fire then went across the harbour to create Ōtarahaka/the Remarkable Dykes at the head of Waiake Stream, Teddington. The area where Tamatea received the warming fire became known as Te Ahi a Tamatea. Later it was named the Giant’s Causeway by the European settlers and in recent years Rāpaki Rock.

From the fifteenth century onwards, Whakaraupō attracted Waitaha, Ngati Mamoe and finally Ngai Tahu. With the bountiful food resources of Whakaraupō in his sights, Ngai Tahu warrior chief Te Rakiwhakaputa landed his waka on a sheltered beach, took off his rāpaki (waist mat), and laid it on the ground as his claim to the area which thereafter was known as Te Rāpaki o Te Rangiwhakaputa. When the chief moved on to claim other land, he left his son, Te Wheke, to establish and defend the fledgling kaika of Rāpaki.

Foot trails connected Rāpaki Māori with settlements at Pūrau, Koukourārata, Wairewa, Takapūneke,Taumutu, Kaiapoi and further afield over the length and breadth of Te Wai Pounamu. But travel about the harbour and peninsula by waka, so easily drawn up on sandy beaches, must have been favoured. No need for jetties. Rather there were traditional landing places known as tauranga.

|

| Upper portion of Port Cooper from hills behind Rāpaki April 1844. John Wallis Barnicoat, University of Otago, Hocken Collections |

|

| Waka drawn up on the beach at Pūrau. The Maori Settlement, Purau Bay, Port Cooper. Richard Aldworth Oliver, 1850, Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū. |

The main attraction of Whakaraupō must have been the plentiful kaimoana. The beaches were a reliable source of pipi and tuaki /cockles gathered by women and children. Rocky outcrops hosted mussels and pāua. Fish were caught in rock fish traps where they were left exposed by the receding tide. Net-fishing provided pātiki (flounder), pioke (rig), kōiro (conger eel) and red cod. Racks and racks of drying pioke were a common sight. Huge nets were worked by men in waka, catching shoals of fish with the flood tides. This would include aua (yellow-eyed mullet) which gave the Māori name of King Billy Island.

Ōtamahua/Quail Island was a favoured source of food. The rocky cliffs were covered with seagull and other seabird nests and were also home to tītī (mutton birds). Pūtakitaki (paradise ducks) were hunted during their moulting period when flight was impossible. Pārera (grey duck), kukupako (black teal), tataa (brown duck) and pāteke (brown teal) were pursued all around the shores of Te Waihora (Lake Ellesmere). There were also kererū, kāka, tūī and weka. Manuhuahua (birds cooked and preserved in their own fat and tied up in sea-kelp baskets) were a large part of the winter food supply.

|

| Shellfish gathering at Rāpaki. WA Taylor Collection, Canterbury Museum |

So the kaika at Rāpaki thrived. As the pressure on resources increased, Ngāi Tahu at the head of Whakaraupō of necessity became well-seasoned travellers and traders. There were frequent trips over Te Tara o Te Raki Hekaia/Gebbies Pass to trap tuna (eels) at Te Waihora and Wairewa. Produce flowed to and from from southern areas, up the coast, down to Raekura/Redcliffs, across the estuary and up the coast again to the pā at Kaiapoi. There were seasonal expeditions using the well-used trails to the Mackenzie Country for the annual weka hunt, to Rakiura (Stewart Island) for tītī or to Te Tai Poutini/Westland for pounamu (greenstone) to trade.

The arrival of European sealers, whalers and flax traders opened up opportunities for trade, for the acquisition of European technology (especially whaling longboats), for employment on whaleboats and at shore stations and for the growing of new food sources such as mutton, pork and potatoes. Gardens were planted and extended. Firewood and flax fibre were in demand. Māori at Rāpaki traded with whalers at Waitata/Little Port Cooper and Koukourārata/Port Levy.

This wave of opportunity was shattered by the intertribal kai huanga feud, the subsequent raids of the Kapiti-based Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha, the introduction of European diseases to which Māori had no immunity and the almost total loss of land (meaning the loss of mahinga kai or food-gathering places) to the predatory New Zealand Company. Regardless of their reduced numbers and circumstances, Māori at Rāpaki adapted to their changed circumstances. They grew crops (mostly wheat and potatoes) and raised pigs, cattle and horses for sale at Ōhinehou/Lyttelton. The men gained employment in the flurry of construction accompanying European settlement. This included work on the challenging Lyttelton–Sumner road over Evans Pass (just reopened!) and the bridle path to the head of the harbour, as well as construction of the Christchurch-Lyttelton rail tunnel and on the wharves.

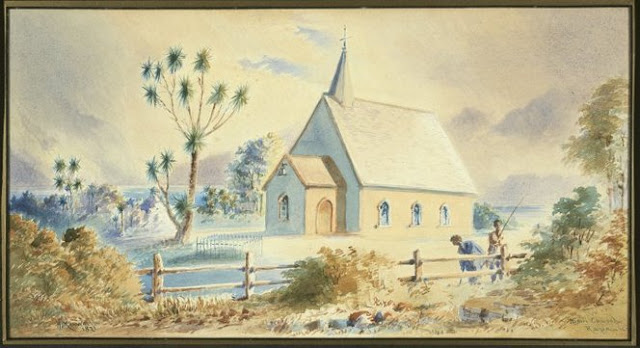

|

| William Henry Raworth, Maori Church Rapauki. 1871. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington |

|

| Te Wheke Hall, new Maori meeting house at Raupaki on opening day, 30 December 1901. CCL |

|

| The church at Rāpaki, Port Cooper. W. A. Taylor, Canterbury Museum |

Transport into and out of Rāpaki was by foot, canoe or, later, horse and trap – though road access was poor and subject to slipping. Like many of the small settlements around Whakaraupō the possibility of a jetty to facilitate access didn’t arise until the very early years of the twentieth century. In January 1902 a letter to the Lyttelton Harbour Board, signed by the Rāpaki residents, asked the Board ‘can you erect a Jetty at our Pah?’

As with so many requests for small settlement jetties in the harbour, the Board stalled. The Harbourmaster, asked by the Board about the likely usage of such a jetty replied: “I may safely say that I do not think it would be used once a year. As all the natives have their horses and traps to drive in and out.”[1] A costing was nevertheless done for a 96 x 8ft jetty and a 120ft ‘approach’ which would enable 5ft of water at the steps at low tide. The total cost was estimated to be £316.10. On the basis of such cost, the Harbour Improvement Committee declined approval.

Undaunted, the community at Rāpaki petitioned the Harbour Board again the following year. This time they pointed out that for many years they had been paying charges on goods to the Harbour Board “without having any advantage therefrom.”[2] They wanted the steamers that regularly plied the harbour to be able to land goods and passengers.

One of the sticking points for the Lyttelton Harbour Board at this time was the fact that the foreshore was not vested in the Board and that consequently, the Board could not recoup costs by charging for the use of jetties. The response to this second petition was that “the question stand over pending the vesting of the foreshore in the Harbour Board.” This occurred in 1905 (hence a flurry of harbour jetty-building shortly thereafter) but there was no apparent further follow-up with Rāpaki by the Board.

My thanks to Donald Couch, Ngai Tahu, Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke and Andrew Scott, General Manager Te Hapū o Ngāti Wheke for their generous assistance.

[1] Lyttelton Harbour Board, general correspondence Rāpaki jetty, Archives NZ/ECan XBAA CH518, Box 798

[1] Lyttelton Harbour Board, general correspondence Rāpaki jetty, Archives NZ/ECan XBAA CH518, Box 798

[2] Ibid

Comments

Post a Comment