Ōtamahua/Quail Island: A little background...

In a harbour rich with stories, Ōtamahua/Quail Island boasts more than its fair share. It has been a place of sustenance and of sadness and has reinvented itself many times over the past 170 years. The stories in this post, about Māori use of the island and the Ward brothers brief sojourn, predate the existence of any jetty but are essential in setting the scene.

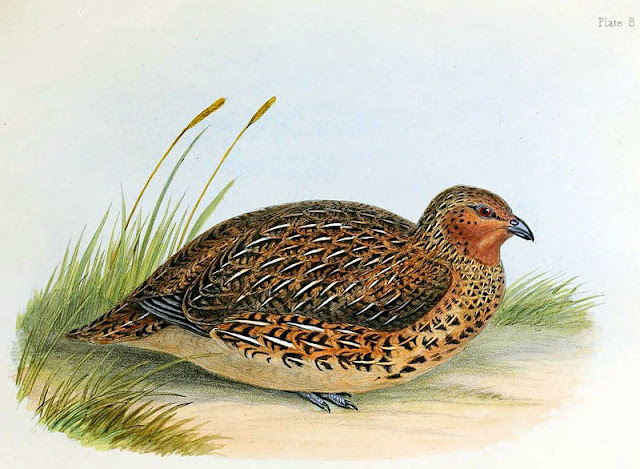

While Māori did not have a permanent settlement on Quail Island, the names Ōtamahua (the place where children collect seabird eggs) and Te Kawakawa (the ‘pepper tree’) tell us much about the island’s pre-European resources. It is ironic that this large island in the upper reaches of Whakaraupō/Lyttelton Harbour should be named by European settlers after a native New Zealand bird that was declared extinct 1875 and, briefly, after the Reverend George Robert Gleig, member of the Canterbury Association Committee, who never set foot in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

| |||||

|

Māori from Rapaki and other settlements in Whakaraupō had no need of jetties. Their waka could be beached on any convenient sandy/shelly shore. Ōtamahua, with its sheltered, sandy beaches on the southern side and shelly beach to the south-west, facing Aua/King Billy, was an important source of mahinga kai, in particular kaimoana (seafood) and manu (birds). Huge kupenga (fishing nets) made of harakeke (flax) were used for catching pātiki (flounder), pioke (dogfish shark or rig), kōiro (conger eel) and Quail Island groper. An early sea captain reported a net stretching from Rapaki to Ōtamahua. Cowan described vividly the hapū cooperation required to manage such large nets, working from the beach at Rapaki:

great flax nets fully quarter of a mile long used to be made for the catching of shark…These immensely long seines were fully six or eight feet deep and were worked by canoes, which would take one end out into mid harbour, the other being made fast, and sweep the great kupenga around the shoals of fish making their way up the harbour with the flood tide. Huge quantities of sharks and other fish were caught in this manner, a fishing fashion which was only possible under the old tribal system when the whole strength of the hapu was available for such tasks.[1]

The Port Cooper District purchase of August 1849 extinguished Māori title to all land in the Port Cooper area (with the exception of three small reserves). This included Ōtamahua although Māori did challenge its inclusion in the purchase. Arriving on the Charlotte Jane, brothers Edward, Henry and Hamilton Ward from Killinchy, Northern Ireland won the ballot for Ōtamahua/Quail Island and decided to farm there.

|

| Edward Ward from a daguerreotype made in 1849. Canterbury Museum |

The oldest brother Edward Ward (24 when he arrived, with brothers aged 19 and 15) wrote in his journal.

In the afternoon explored Quail Island by boat and found it really well fitted for settling in – fine rich grass, soil, abundant springs of water and a beautiful site for a house. We thought light of several inconveniences condequent of such isolation...Its advantages are a pretty site, closeness to the port market, besides good grass run for cows, without the trouble of fences or fear of straying far away; pleasant too in being on the sea and a likely place for fishing and shooting.[2]

The brothers needed a boat. Edward Ward oversaw the building of a 1-ton, 24-foot yawl Lass of Erin. On March 13 1851 he announced...

Six of us carried her down and launched her from the beach opposite Crawford’s. Andy, Robert, Hamilton and I were her crew, and we rowed out a short way, then set the sail and tacked across and across the harbour with the sail at first reefed. Though the wind blew hard and there was a little sea she behaved gallantly, both with oar and sail.

Five days later Edward and Hamilton took six goats over to the island on the yawl. Building materials for the house under construction on the island were brought over the same way. Since there is no indication in Edward Ward’s journal that they built any sort of jetty on the island, they presumably ran the yawl up on the southern beach (where visitors now swim) at high tide. This is confirmed in the journal when Ward writes...

At twelve o’clock took cargo of piles and house frame in the yawl to the Island, putting ashore at the inner bay [my italics]...We returned with but one tack, holding our wind well across, though it was blowing right into the harbour; but it was an ebb tide. It is of no use to attempt it from the point of the Island if the tide is flowing.[3]

Building material accumulated on the beach until a road was constructed up the hill to the house site. On 31 March “I ...had the satisfaction of seeing before I left the Island, the bullock, ‘Big Thomas’, take his first load of ‘house’ up the new road.”[4]

|

| View from terrace in front of Mr Fitzgerald’s house at Lyttelton, 15 November 1852. You can see the Ward brothers' house on Quail Island. JE Fitzgerald watercolour, Canterbury Museum, 1938.238.33. |

Things didn’t always go so smoothly. In April Edward and a companion tried taking a load, which included the shingler who had been working on the house, across the mud to the ‘outer point’ where they had left the boat. Unfortunately the bullock got badly bogged.

Firewood for their newly built house and for a lime kiln was gathered further up towards the head of the harbour. The yawl would be loaded up with as much wood as could be carried (about 1½ cords) back to the island. Tragically, on Monday 23 June, Edward and Henry set off to gather more firewood. On Tuesday the alarm was raised and the Lass of Erin was found upturned on a beach with firewood drifting about the bay. Both brothers were drowned.

| ||

Ōtamahua/Quail Island cradled within the crater hills. VC Browne & Son, 1973

|

[1] James Cowan, Maori Folk-tales of the Port Hills (Christchurch: Whitcombe & Tombs, 1954), 42.

[2] Edward Ward, The Journal of Edward Ward (Christchurch: Pegasus Press, 1951) 119.

[3] Ibid, 155-6

[4] Ibid, 160

What a read. Fascinating, maddening, exciting, and heartbreaking all in one short post. Fascinating for the history. Maddening for the appropriation of land by Europeans (mirror of the worse and terrible history of the U.S.), exciting for your research project ( to read the journal entries), and heartbreaking, both for the Maori's loss of land, and for the story of the drowned Ward brothers.

ReplyDeleteYou clearly have deep and respectful knowledge of Maori language and history, woven, as it is, throughout your telling of this history. Read every word and tried to pronounce the Maori words and imagine the time.

Thank you for your lovely words Deb. That's very heartening. I certainly don't have deep knowledge of the Maori language. Can't speak Maori at all. But all NZers have incidental Maori in their vocabulary because many words are in common use. More than we realise I think. Acknowledging Maori reo (language) and tikanga (culture) is very important in NZ now (not so in the past). That is progress. Having said that, the topic of jetties is essentially euro-focused; Maori had no need of jetties.

ReplyDelete