Ōtamahua/Quail Island #4: The Leper Colony

There are times when, instead of representing access and adventure, jetties must simply mock those who cannot use them. Islands offer opportunities for quiet retreat but also for incarceration. And so Ōtamahua/Quail Island and Ripapa Island in Whakaraupō were both used to quarantine and imprison, in some cases with little hope of ever regaining freedom.

The saddest use of Ōtamahua/Quail Island extended from 1906 to 1925 when the island was home to men suffering from the contagious, long-term disease leprosy. There was a great public fear of leprosy. The Press, sometime after the first patient was isolated, described it as “a living death”.[1] At one point nine men were contained in the ‘Leper village’ on the hillside above the second swimming beach. They were not permitted off the island nor to roam far from the area immediately adjacent to the hospital and leper cottages.

The saddest use of Ōtamahua/Quail Island extended from 1906 to 1925 when the island was home to men suffering from the contagious, long-term disease leprosy. There was a great public fear of leprosy. The Press, sometime after the first patient was isolated, described it as “a living death”.[1] At one point nine men were contained in the ‘Leper village’ on the hillside above the second swimming beach. They were not permitted off the island nor to roam far from the area immediately adjacent to the hospital and leper cottages.

|

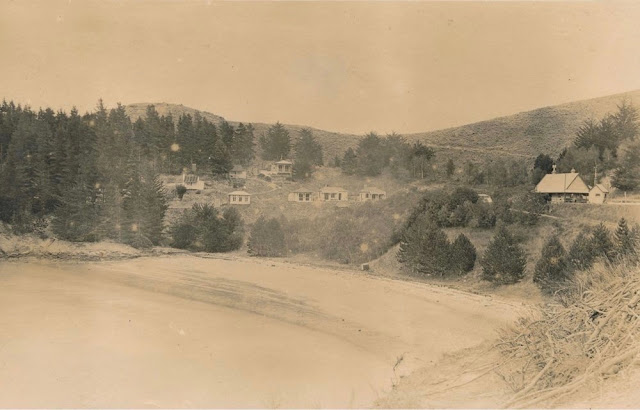

| View over the caretaker's (later nurse's) cottage garden to the colony huts and bungalows with the recreation hall on the far right, c. 1923, unknown photographer. Lyttelton Museum, Ref Z1072 |

The first leprosy patient, Will Vallane, was isolated on Ōtamahua/Quail Island in 1906. A doctor's visit once and month and occasional visits from relatives were all the human contact he had, apart from the island caretaker who fed and provided for him. To make matters worse he was lodged in the hospital building - formidable accommodation for a man alone. The following year the Department of Health built a hut for Will and in November 1908 he acquired his first company in the form of Timothy Kokiri, the second leprosy patient on the island.[2] Tim Kokiri was declared cured in 1909 and discharged. However, having apparently been rejected by his family in Tauranga he chose to return to Quail Island to care for the ageing and increasingly blind Will Vallane. As more patients arrived, further small huts were built to accommodate them.

While the establishment of a leper colony on the island is not directly connected with the two jetties which were constructed in an earlier period, it is worth reflecting on what those jetties might have meant to the men. On a recent visit to Ōtamahua/Quail Island I stood at the entrance to a reconstructed cottage, looking out at the beautiful view. In the centre distance was the stock jetty. Every day the men would have seen arrivals and departures. They would have watched the comings and goings of the Antarctic expedition animals and men. They saw the world passing by knowing that such freedom was denied them. They were not even able to walk down to the jetty, so close to their small village.

There were visitors. The Lyttelton doctor came across regularly, sometimes with other health officials. From time to time local parishioners gathered on the island for a church service. On one occasion a party of singers shipped a piano over to the island in the launch John Anderson. They landed at the stock jetty and lugged the piano up the hill to the quarantine station buildings where they sang a variety of sacred and popular songs. Rāpaki Māori would also visit. However, with the exception of the medical staff, all visitors were required to keep a 'safe' distance. In many ways the patients were little better than prisoners on the island.

Shortly before the leper colony was officially disestablished, two events occurred which were designed to improve the quality of life for the patients. One was the arrival of a new recreation hall. This was an ex-Defence Department guard house which had stood on a wharf at Lyttelton since the early years of World War 1. The contractor, instead of dismantling and re-erecting the 9-ton building, chose to transport it in one piece on a pile-driving pontoon along with a crane which was used to unload the building, not at the jetty but directly onto the beach at Quail Island. From there it was winched 50 chains to its final location. The second event involved the Director General of the Health Department, Hester Gentles, recommending that a rowing boat be provided for the men. This was purchased by public subscription and moored off Lepers Beach (now known as Skiers Beach). There may have been a small jetty adjacent to the boatshed built to house the craft.[4]

Despite these improvements, one patient was unwilling to wait. It seems George Wilson Phillips may have contracted leprosy when he was a soldier on active service in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Advance Party in Samoa in 1916. He had a mild form of the disease and, having spent nine years on Ōtamahua/Quail Island, decided to leave in January 1925. One account has Phillips arriving at Orton Bradley's homestead in Charteris Bay at 11.00pm one night, dressed as a clergyman. There he rang for a taxi and headed for Christchurch which was the last anyone saw of him.[5] This begs the question as to how Phillips got from the island to the mainland - it could only have been by boat (maybe the newly acquired rowboat?) and probably only with help.

The leper colony on Ōtamahua/Quail Island was finally closed when the eight remaining patients were transferred to a similar but much larger colony on Makogai Island in Fiji in August 1925.

If you are interested in finding out more about the leper colony - or about Ōtamahua/Quail Island in general, Peter Jackson's book is a great read. The printed book has, more recently, been supplemented with an e-book by Lindsay J. Daniel, Companion to Ōtamahua-Quail Island,: A link with the Past, available from the Ōtamahua-Quail Island Restoration Trust as an e-book.

While the establishment of a leper colony on the island is not directly connected with the two jetties which were constructed in an earlier period, it is worth reflecting on what those jetties might have meant to the men. On a recent visit to Ōtamahua/Quail Island I stood at the entrance to a reconstructed cottage, looking out at the beautiful view. In the centre distance was the stock jetty. Every day the men would have seen arrivals and departures. They would have watched the comings and goings of the Antarctic expedition animals and men. They saw the world passing by knowing that such freedom was denied them. They were not even able to walk down to the jetty, so close to their small village.

There were visitors. The Lyttelton doctor came across regularly, sometimes with other health officials. From time to time local parishioners gathered on the island for a church service. On one occasion a party of singers shipped a piano over to the island in the launch John Anderson. They landed at the stock jetty and lugged the piano up the hill to the quarantine station buildings where they sang a variety of sacred and popular songs. Rāpaki Māori would also visit. However, with the exception of the medical staff, all visitors were required to keep a 'safe' distance. In many ways the patients were little better than prisoners on the island.

| ||

Leprosy patients on Quail Island in the 1920s. From left to right: Albert (Big Jim) Lord, Tim Kokiri, Auatihio Matawai, Ivon Crispen Skelton, Ah Pat, Joe Apaapa, George Wilson Phillips and Dr Charles Upham. Absent Will Vallane and Ah Yip. Canterbury Museum

|

Despite these improvements, one patient was unwilling to wait. It seems George Wilson Phillips may have contracted leprosy when he was a soldier on active service in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force Advance Party in Samoa in 1916. He had a mild form of the disease and, having spent nine years on Ōtamahua/Quail Island, decided to leave in January 1925. One account has Phillips arriving at Orton Bradley's homestead in Charteris Bay at 11.00pm one night, dressed as a clergyman. There he rang for a taxi and headed for Christchurch which was the last anyone saw of him.[5] This begs the question as to how Phillips got from the island to the mainland - it could only have been by boat (maybe the newly acquired rowboat?) and probably only with help.

The leper colony on Ōtamahua/Quail Island was finally closed when the eight remaining patients were transferred to a similar but much larger colony on Makogai Island in Fiji in August 1925.

| ||

Shipping the recreation hall to the Quail Island leper colony, 1922, unknown photographer, Nola Muir collection, Lyttelton Museum, Ref. Z1133

|

[1] Press, 12 October 1907

[2] Timothy Kokiri was variously known as Tim or Tom Kokere, Jimmy Kokere, James Kokiri and Hemi Kokiri. Lindsay J. Daniel, Companion to Otamahua-Quail Island,: A link with the Past. Otamahua-Quail Island Restoration Trust, 2017. Available as an e-book from the Restoration Trust, https://www.quailisland.org.nz/index.php/shop

[3] Peter Jackson, Otamatua - Quail Island: A link with the past. Department of Conservation, 2nd ed 2006, p. 42

[2] Timothy Kokiri was variously known as Tim or Tom Kokere, Jimmy Kokere, James Kokiri and Hemi Kokiri. Lindsay J. Daniel, Companion to Otamahua-Quail Island,: A link with the Past. Otamahua-Quail Island Restoration Trust, 2017. Available as an e-book from the Restoration Trust, https://www.quailisland.org.nz/index.php/shop

[3] Peter Jackson, Otamatua - Quail Island: A link with the past. Department of Conservation, 2nd ed 2006, p. 42

[4] Lindsay J. Daniel, Companion to Otamahua-Quail Island,: A link with the Past.

[5] Peter Jackson, Otamatua - Quail Island: A link with the past, p. 42

[5] Peter Jackson, Otamatua - Quail Island: A link with the past, p. 42

Comments

Post a Comment